Remdesivir could be a new weapon in the fight against the coronavirus pandemic. Dr. Anthony Fauci believes the FDA will eventually give the go-ahead for emergency use of the drug to fight COVID-19. Temple University Doctor Gerard Griner has conducted trials of the drug and spoke to NBC10’s Erin Coleman about its potential.

Two local hospitals were involved in trials of an experimental drug that may help patients afflicted with the coronavirus.

The drug remdesivir, produced by Gilead Sciences, showed reduced recovery times for patients with severe cases of Covid-19, the disease caused by the virus.

In the trial, patients on remdesivir recovered almost three days sooner than those treated with a placebo, meaning they did not receive the drug. And the percentage of patients on the drug who died was smaller than the placebo.

The National Institutes of Health quickly enrolled more than 1,000 hospitalized patients, including locally at Temple University Hospital, the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania and Penn Presbyterian Medical Center.

“They put up so many sites so we can get the numbers, so we can get the answers,” said Dr. William Short, who led Penn’s involvement in the trial.

NIH was only expected to enroll 400, before securing the number of patients over 1,000. It all unfolded at a quick pace. Worldwide, a slew of clinical trials are underway for drugs that can treat the virus.

“The data shows that remdesivir has a clear-cut, significant, positive effect in diminishing the time to recover,” Dr. Anthony Fauci, the federal government’s top infectious diseases expert, said in Washington this week. “This is really quite important.”

On the same day, The Lancet, a medical journal, published results of a separate Chinese study that found no definite conclusion that the drug was effective.

“That was an underpowered study,” Short said. Health researchers there had trouble getting enough people to test due to a declining number of cases following strict lockdowns. “Their curve had gone down,” Short added.

At this point, the interim analysis of the NIH data - the results that generated Fauci's positive response - is based on 400 patients who have recovered. Some are still in the hospital. Eight percent of the patients on remdesivir died compared to 11 percent who were not treated with it.

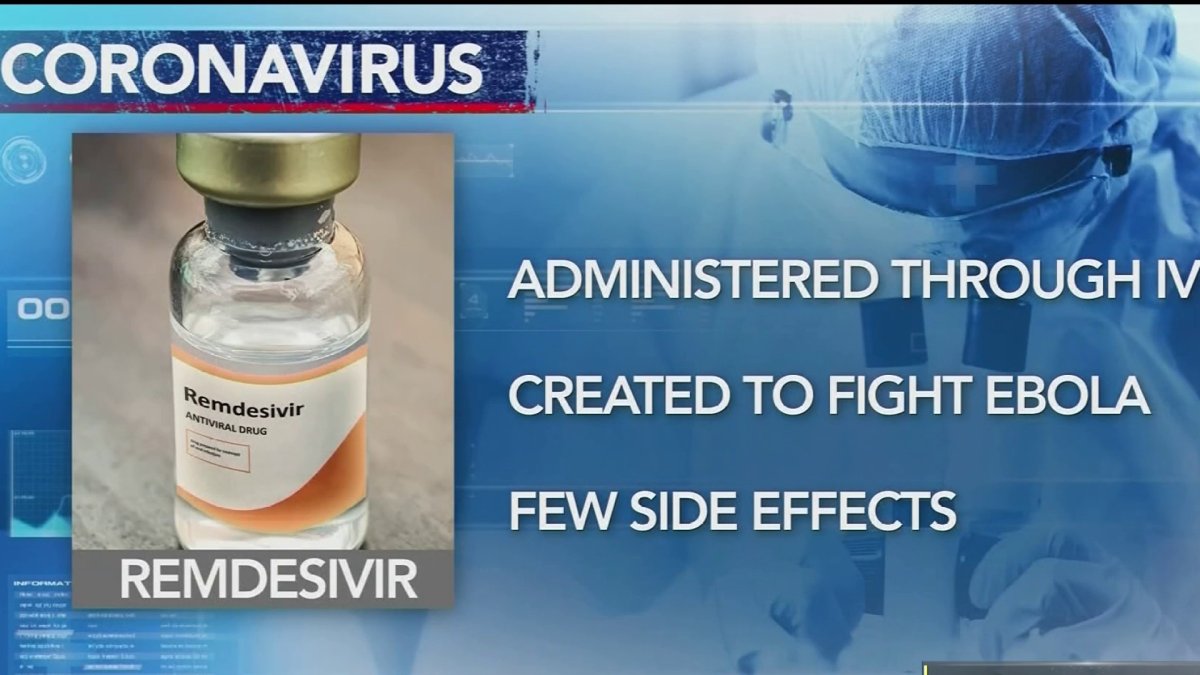

The drug was initially developed to treat Ebola but did not prove to be effective. At the start of 2020, Gilead was only making enough remdesivir to treat 5,000 patients, a company statement says. It's ramping up production to make enough doses for more than 140,000 patients by the end of May, and more than 1 million by December 2020.

Remdesivir will now be a standard of care going forward, and researchers are looking at comparing other drugs versus a placebo for patients who are already on remdesivir, Short said.

Mike Dewan, of Worcester, was treated with remdesivir for the coronavirus at Penn Presbyterian, where he spent 17 days on a ventilator.

When his battle with the virus started, he had a fever and chills. But it got worse.

“I had that dry cough that they described, and it just got worse and worse, and then...I was having trouble breathing,” he said.

He thinks the treatment with remdesivir helped.

“We didn’t know, there wasn’t a lot of data out. But the last few days, these studies are coming out that are very positive,” he said.

“Overall, these results are encouraging,” Dr. Gerard Criner, who led the trial at Temple, said in a live interview Thursday with NBC10.

The drug seemed to prevent the virus from replicating, but does not address other issues from the virus like lung inflammation, he said.

“I think it’s one of the parts of the treatments that are important,” Criner said. Other treatments might be needed, perhaps one of the 18 that Temple Health is trying out at the moment.

“I think in the future, it’s going to be combination therapies,” he added.