North Korea's recent abrupt push to improve ties with South Korea wasn't totally unexpected, as the country has a history of launching provocations and then pursuing dialogue with rivals Seoul and Washington in an attempt to win concessions.

Still, Tuesday's planned talks between the Koreas, the first in about two years, have raised hopes of at least a temporary easing of tensions over North Korea's recent nuclear and missile tests, which have ignited fears of a possible war.

A look at how the Korean talks were arranged and what to expect from them:

KIM JONG UN'S OLIVE BRANCH

In a New Year's Day speech, North Korea's young leader, Kim Jong Un, said he was willing to send a delegation to next month's Winter Olympics in South Korea, while also announcing he has a "nuclear button" on his desk that could launch an atomic bomb at any location in the mainland United States.

Critics called Kim's mixed message a gambit to drive a wedge between Seoul and Washington, weaken U.S.-led international pressure and buy time for North Korea to perfect its nuclear weapons. Sanctions imposed by the U.N. and individual nations were toughened after North Korea's sixth and biggest nuclear test and three intercontinental ballistic missile launches last year.

Liberal South Korean President Moon Jae-in, who seeks rapprochement with North Korea, quickly responded to Kim's outreach by offering talks at the border village of Panmunjom to discuss Olympic cooperation and overall ties. Kim accepted Moon's proposal.

U.S. President Donald Trump on Saturday called the talks "a big start," saying he hopes for some progress from the negotiations. He earlier responded to Kim's New Year's Day address by warning that he has a much bigger and more powerful "nuclear button."

U.S. & World

Stories that affect your life across the U.S. and around the world.

OLYMPIC COOPERATON

South Korean officials say they will focus in the talks on Olympic cooperation before moving onto more difficult political and military issues.

Moon's government wants North Korea to participate in the Feb. 8-25 games in Pyeongchang, South Korea, in hopes of reducing animosities between the rivals, which are separated by the world's most heavily fortified border. South Korea may suggest that North and South Korean athletes parade together during the opening and closing ceremonies and field a joint women's ice hockey team.

Athletes from the two Koreas took similar steps at international sporting events during an earlier era of inter-Korean detente. But such symbols of reduced animosity would receive widespread attention at Pyeongchang after a year of heightened nuclear tensions during which Kim and Trump traded threats of nuclear war and crude personal attacks.

But North Korea, which is weak in winter sports, currently has no athletes qualified to participate in the Pyeonghang Games. It needs to receive an additional quota to compete, and its International Olympic Committee representative, Chang Ung, headed to Switzerland over the weekend for talks with IOC officials, according to Japanese media.

South Korea is also expected to ask the IOC to allow North Korea to attend the games.

OBSTACLES

While it is possible that the two Koreas will agree on the North's participation in the Olympics, they are likely to differ sharply over other issues relating to how to improve ties.

Moon's government wants to resume temporary reunions of families separated by war and work out measures to reduce threats in frontline areas. But North Korea could demand some rewards in exchange for those steps, such as the revival of stalled cooperation projects that are lucrative for the North or the suspensions of annual U.S.-South Korean military exercises that it calls a rehearsal for an invasion.

The drills' suspension is something that South Korea cannot accept in consideration of its relations with the U.S., its main ally, which is seeking increased pressure and sanctions on the North.

The Trump administration has agreed to delay upcoming springtime drills with South Korea until after the Olympic Games. But Defense Secretary Jim Mattis has insisted the delay is a practical necessity to accommodate the Olympics, not a political gesture.

An agreement by South Korea to revive a jointly run industrial park or a tourism project could also draw criticism from abroad that it violates U.N. sanctions because they would result in South Korean money being sent to North Korea, critics say.

Analysts say tensions could flare again after the Olympics, with U.S. and South Korean troops carrying out their delayed drills, and North Korea likely responding with new weapons tests.

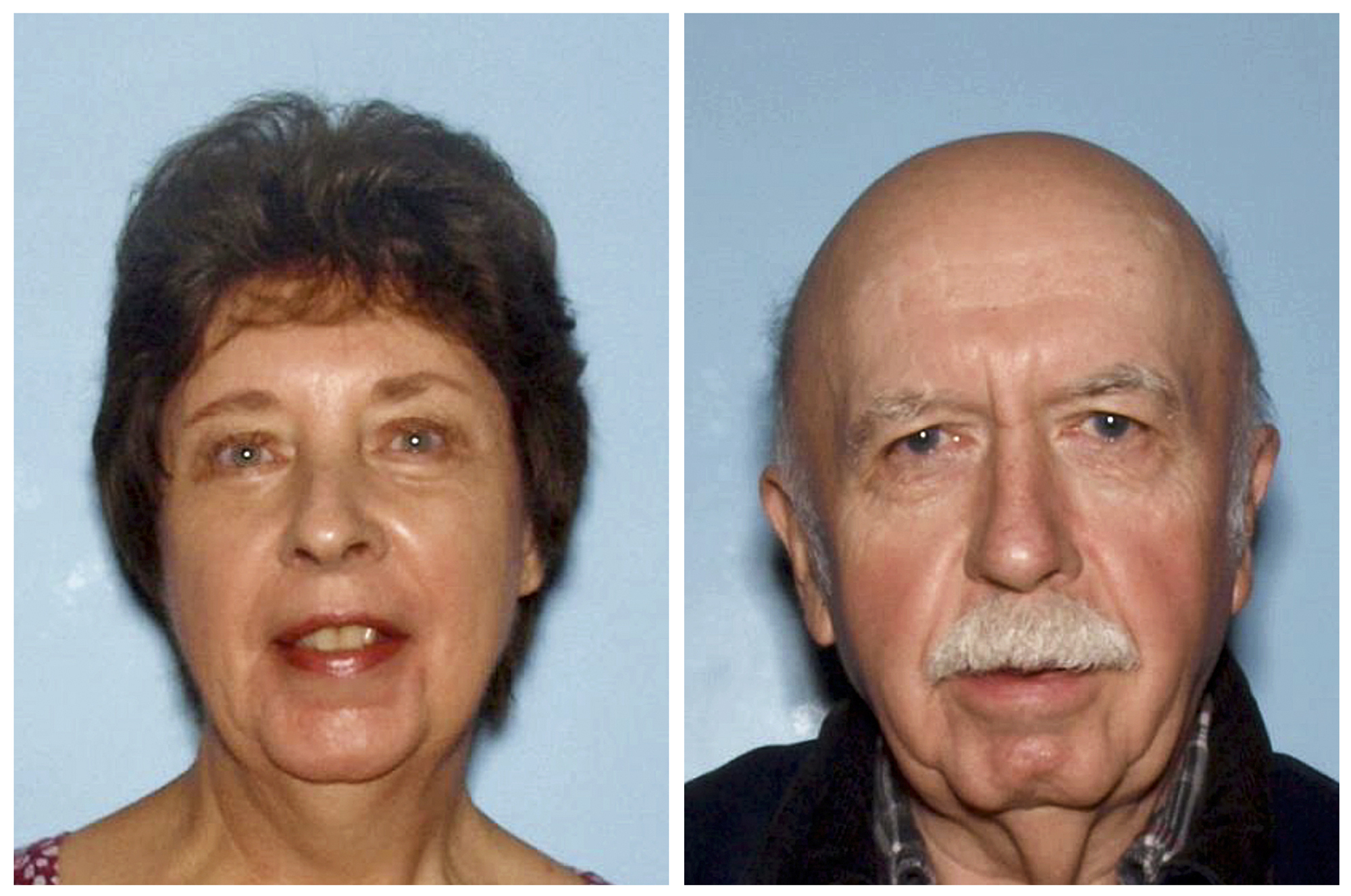

The North Korean delegation is headed by Ri Son Gwon, a hardliner who heads a government agency that handles relations with South Korea. Ri is known as a close associate of senior Workers' Party official Kim Yong Chol, who Seoul officials believe was behind two attacks in 2010 that killed 50 South Koreans. South Korea is sending its top official on North Korea, Unification Minister Cho Myoung-gyon.