A Delaware judge is hearing testimony in a lawsuit alleging that officials are failing to provide adequate educational opportunities for disadvantaged students, partly because local school property tax collections are based on assessments that are decades old.

A two-day trial began Wednesday in Chancery Court, pitting attorneys for the NAACP and a group called Delawareans for Educational Opportunity against lawyers representing the state's three counties.

A separate trial in which state officials are named as defendants will be held later.

The lawsuit says inadequate funding has contributed to the dismal performance on standardized assessments among children from low-income families, children with disabilities, and children whose first language is not English. Those students, collectively described as "disadvantaged," number in the tens of thousands.

In refusing a request by state officials last year to dismiss the lawsuit, Vice Chancellor J. Travis Laster said allegations regarding how the state allocates financial and educational resources, and how disadvantaged students have become re-segregated by race and class, suggest that Delaware's public education system has "deep structural flaws." He said those flaws are profound enough to support a claim that the state is failing its constitutional mandate to maintain a "general and efficient" school system that serves disadvantaged students.

Among the allegations in the lawsuit is that property in Kent, New Castle and Sussex counties is not being assessed for tax purposes at its "true value in money" as required under state law. The plaintiffs say that results in less tax revenue than what schools should be getting.

The plaintiffs, joined by the city of Wilmington, are asking the judge to declare that the counties are violating Delaware's constitution and state law by not assessing properties at fair market value. The most recent assessments were done in 1987 in Kent County, 1983 in New Castle County and 1974 in Sussex County. While state law requires that property be assessed at fair market value, it does not require that counties conduct reassessments on any particular schedule.

Local

Breaking news and the stories that matter to your neighborhood.

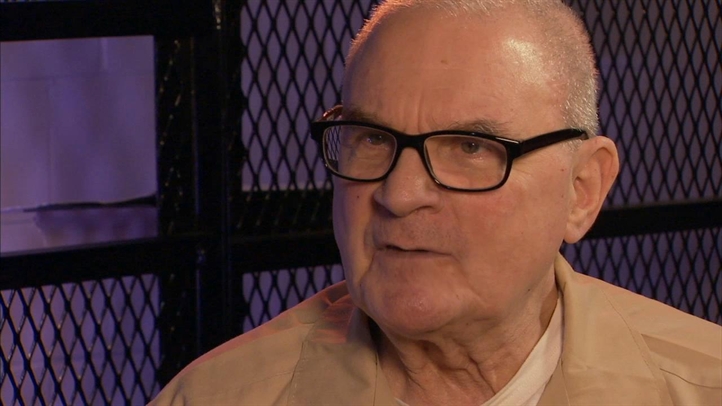

"The absence of school funding has made city schools, especially, perform at their lowest level in history," New Castle County councilman Jea Street, president of Delawareans for Educational Opportunity, told Laster.

Street added that ignoring the academic needs of disadvantaged children has also led to them being unfairly subjected to disciplinary measures, including suspension and expulsion.

"If you can't perform in school, then you're not likely to be a model child," said Street, adding that adequate funding for disadvantaged students could help break the "school-to-prison pipeline."

The counties argue that Street's group and the NAACP have no standing to bring claims regarding property assessments and taxation because those issues are not germane to the organizations and they have failed to show they have been injured. The counties also contend that the organizations have not shown that any of their members are being directly harmed by the alleged failure of the counties to assess properties at their true value.

Nicholas Brannick, an attorney for New Castle County, pointed out that Street voted against a proposed countywide reassessment in 2015.

In a deposition, Street said he couldn't recall why he voted against reassessment. In court, he testified that he wasn't focused on county taxes at the time, and that his priority was getting a new library built.

In other testimony, an expert in property assessment said he concluded after conducting a study for the plaintiffs that current assessments in all three counties are much less than current market values, and that they are inconsistent with the standards of the International Association of Assessing Officers.

Richard Almy also testified that the current assessment systems used by the counties are regressive.

"High-value properties are assessed at a lower percentage of their value than are low-value properties," he explained.

Testimony was to resume Thursday.