In an 1987 television interview, the former general manager of the Los Angeles Dodgers said Black people can't swim because they aren't buoyant.

That couldn't be further from the truth.

Water has always been part of African life.

Paul Best, a historical consultant for the Independence Seaport Museum in Philadelphia, says water was part of African rituals and religions.

Get Philly local news, weather forecasts, sports and entertainment stories to your inbox. Sign up for NBC Philadelphia newsletters.

"They had deities called Orishas. So Obatala, Yemaya, Oshun, these were gods of rivers and bodies of water,” Best says.

African nations along the coast were home to expert divers, swimmers and boatmen.

They were so skilled that Africans were sought out by enslavers during the trans-Atlantic slave trade.

Local

Breaking news and the stories that matter to your neighborhood.

A plaque at the Fairmount Water Works' exhibit called "Pool: The Social History of Segregation,” explains that the swimming skills of American Blacks far exceeded those of white Americans well into the 19th century.

A racist cliche that Black people can't swim is often traced to the Middle Passage when Igbo warriors chose death by water once the ships landed at Dunbar Creek on St. Simons Island in Glynn County, Georgia in 1803.

Several dozen warriors who were masters of the sea chose to jump from the slave ships and sank to the bottom of the ocean as a protest to being enslaved.

“The water after (that) turns into this sacred space, this place of pain and trauma,” Best says. “We then see it turn into a place of freedom because they also had people who were escaping through the same passage, the Middle Passage escaping, and moving back to Africa to start lives again."

The Africans who chose to stay in the Americas influenced American maritime trade.

Their stories are among the many that are part of Philadelphia's long, deep African American history. NBC10's “Race in Philly” special, airing Tuesday, Aug. 23 at 7:30pm, and viewable afterward on this page on NBC10.com, is highlighting some of these stories. Black history in Philadelphia stretches from the founding of the country through the 21st century.

Africans Influenced American Maritime Trade

After emancipation, Africans "took jobs in maritime trade. And so, in the early 1800s, American shipping was booming exponentially. At that time, about 100,000 men were sea workers, and a fifth of them, about 20,000, were Black men,” says Best, of the Independence Seaport Museum.

Black sea workers took jobs as oystermen, boatmen, fishers and whalers, and thanks to the Delaware River, Philadelphia grew rapidly throughout the 19th century.

"The role of sea work for Black people turned into this foundation for our communities,” Best says. “The money that they used supported the homes and supported Black communities."

As American maritime trade boomed, so did immigration.

This kind of migration was not forced by enslavers, but by nature.

Helena Olea, associate director of programs in Alianza America, says, "The lack of water, precisely the dry season, has impacted particular areas of both Central America and Mexico, and it’s a cause why many migrate. In others, it’s the excess of water: rainfalls, hurricanes that in some cases destroy their homes.”

Saturnino "Nate" Garrido has called Philadelphia home for more than 30 years.

He left his home in the Dominican Republic at 25 years old seeking a better life in the United States.

After being denied a green card, Garrido got on a homemade wooden boat with more than 50 migrants leaving the Dominican Republic.

He nearly drowned after his boat capsized from bad weather on that trip.

He was taken back to the Dominican Republic.

On his second trip, he successfully made it to Puerto Rico, before catching a plane to New York.

He lived for a few months there before relocating to Philadelphia permanently.

Throughout the years, thousands of immigrants have died on the same journey Garrido took through the Mona Passage.

He saw migrants drown fighting for freedom, but he said he'd risk everything again for his family.

“The water symbolizes for me life,” Garrido said.

Now, he says his family is now better off for his sacrifice.

He did, however, face discrimination because of how he got to the United States.

“They call you wet, in Spanish ‘mojado,’” Garrido says.

Nelly Jiménez, CEO of Aclamo says, "There are a lot of traumas that a lot of people that are crossing the border go through. Even if they are successful, they see other people falling, staying behind and there is nothing that they can do. They want to belong, they want to be respected, they want to work.”

It’s a similar struggle African Americans faced.

Although they were long masters of the water, they were stripped of their connection to it during the Jim Crow era.

Public pools were segregated. After integration, many public pools closed and private pools or swim clubs opened with "whites only" as a policy.

The outcome was devastating.

“A lot of those folks were not able to access pools in their neighborhoods,” Zindzi Harley, curator at Philadelphia’s African American Museum says, “possibly due to the fact that they were predominantly white institutions that were frequented by white community members that didn't want them in those spaces.”

She says that's why we see the disparities among Black youth when it comes to not being able to swim and having higher mortality rates when it comes to drowning.

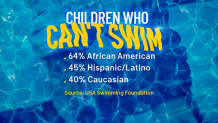

According to the USA Swimming Foundation, 64% of African American children can't swim.

Compare that with 45% of Hispanic and 40% of white children unable to swim.

Studies show the drowning rate is 5 1/2 times higher for Black children than white children ages 5 to 19.

Cullen Jones, four-time Olympic medalist and the first African American to hold a world record in swimming, almost drowned at Dorney Park in Lehigh County, Pennsylvania.

Now, he's one of the fastest swimmers alive.

Cullen Jones and Simone Manuel are breaking records and smashing stereotypes in swimming.

To this day, swimming is a predominantly white sport.

But community leaders are working to change that narrative.

Barriers to Pool Access Bore Ingenuity

The Nile Swim Club in Yeadon, Pennsylvania, surfaced when Black people were denied access to segregated pools.

The current president of the swim club says, "Instead of some of those members fighting and protesting to join that swim club, they came back to our community and said let’s open our own swim club".

In 1959, the nation's first private swim club owned and operated by African Americans opened just outside of Philadelphia.

It helped swimming become a way of life for generations of local families.

For the families who had to rely on city pools, barriers were based on their zip codes.

Today, the city Department of Parks and Recreation manages 70 outdoor pools throughout Philadelphia.

It offers swim lessons at the pools that are open.

Finding an open pool has been a challenge in recent years.

The city was short 85 lifeguards and 90 pool attendants for this season.

As of Aug. 1, 25 city-run pools were closed, with nearly a dozen more closing soon, well before the summer ends.

The last city pool closes on Sept. 7.

Kathryn Ott Lovell, city parks and recreation commissioner, says her department decides which pools to open and close based on geography and equity.

“We certainly, certainly paid attention to race,” she said. “But most importantly, we paid attention to those communities where there's a high heat vulnerability and a high crime level, you know, where violence prevention is going to be a real opportunity through pools.”

But NBC10 showed the commissioner a map displaying where most city pools are closed: predominantly black and brown communities.

She says the reason is because North Philadelphia has a larger concentration of pools, so that area would have more closures.

Still, that leaves areas – like 12th and Cambria street, and North 21st Street and Cecil B Moore Avenue – without pools.

Community leaders say having pools in those areas would help keep youth out of trouble.

Keeping youth away from crime and gangs was one of reasons famed Philadelphia swim coach Jim Ellis started his own swim program.

"I wanted to make a difference in the world,” Ellis says. “Swimming is what I knew, what I love. Swimming was good to me growing up."

In the 1970s, Ellis founded PDR Swim Team at the Sayre Recreation Center pool.

It was the first Black swim team in the country.

His coaching achieved national fame.

Black children from Philadelphia became elite swimmers.

His program was also a pipeline for city lifeguards.

Ellis says having no city-run indoor pools is part of the reason why more youth of color in the city aren’t involved in swimming.

“A pool being opened on a regular basis is where someone can say, 'Hey, this is part of my lifestyle,’” he says, “where a family can say, 'Well, every Friday and Saturday we're going swimming at a pool' that they know they'll enjoy being at. I think that makes a big difference.”

Ellis' program is no longer all Black.

It draws swimmers from all nationalities.

His program is now at the salvation army Kroc Center in Nicetown-Tioga.

Barriers Become Skin Deep

While we've witnessed the success of people of color when they immerse themselves in water, for years and still to this day many have aversions it. That’s because of the impact moisture has on their hair.

Many women won't get into the pool and they avoid workouts.

Water can cause straightened or processed hair to curl back into its natural state, which for a long period of time wasn’t considered socially acceptable.

A recent Nielsen report shows Black people spend nearly nine times more than their counterparts on hair and beauty products.

Letitia Barnes, hair stylist at Rasa Hair Salon in Philadelphia's Germantown neighborhood says, "It’s just because, for lack of a better word, (we are) brainwashed with society and media and movies and how we are [told we’re] supposed to look.”

Rasa Hair Salon styles mostly natural hair that’s locked, twisted or curly.

“It kind of sounds funny because we’ve been born with this hair, but we never actually got the training like what do i do with it,” stylist Alana Sewell says.

The lack of knowledge about Black hair goes back as far as the 1600s.

Slave masters viewed African hair as unruly, unsightly and unmanageable.

To thrive, Black women and men would straighten their hair.

This practice passed down through generations that has affected other areas of life and leisure.

“One of the main excuses for missing a session or rescheduling a session or not starting when they said they wanted to start – maybe pushing it to a different day to start is, ‘Oh girl, I’ve got a hair appointment, I don’t want to sweat out my hair,” Sheena Ohlig says.

Ohlig is an award-winning professional bodybuilder with the International Federation of Bodybuilding and Fitness.

She says, historically, women in her sport wore straight hair, but she's been donning her natural curls as she competes in shows.

She says she's beginning to see a shift with women embracing their natural hair.

"There are a lot more competitors that are wearing their hair more naturally curly, or with the faux locks or with the twists,” Ohlig says. “I think on a more professional level, the H.R. level, the executive level, there has to be change there.”

Embracing natural beauty restores the rights of passage to the water, not just submersion but using water to keep natural hair moisturized daily to avoid breakage.

Water is not just good for our hair, but also our bodies.

In 2017 and 2018, Philadelphia's Department of Public Health did a study in conjunction with the city Department of Parks and Recreation to see what would happen if they switched out old water fountains and replaced them with new hydration stations that keep the water chilled.

"We found that water consumption doubled just with the introduction of this newer higher quality water fountain," according to Mica Root.

Root works with the city’s Division of Chronic Disease and Injury Prevention.

"One of the places where we as the health department have done a lot of work is in conjunction with the school district in schools because studies have shown that even mild dehydration affects children’s ability to learn,” Root says.

From our humanity to our health, water is the one thing that touches all of us.

“There is a strong bond between watermen, regardless of race,” William Wallace, descendant of African American skipjack captains from Deal Island, Maryland, is quoted as saying in the book, “African Founders: How Enslaved People Expanded American Ideals” by David Hackett Fischer. “Water bonds them together.”

Here are community resources mentioned in NBC10’s “Race in Philly: Color of Water” special:

BLJ Community Rowing

Only black-owned rowing company in U.S. sports

Address: 2200 Kelly Dr, Philadelphia, PA 19129

Phone: (845) 282-3463

https://www.bljcommunityrowing.com/

Independence Seaport Museum

Documents maritime history and culture along the Delaware River

Address: 211 S Christopher Columbus Blvd, Philadelphia, PA 19106

Phone: (215) 413-8655

Nile Swim Club

The first Black-owned pool club in the U.S.

Address: 513 S Union Ave, Yeadon, PA 19050, USA

Phone: (610) 623-1535

Email: swimthenile60@gmail.com

PDR Swim

The first African American swim team in the U.S.

Swim meets at two locations: Salvation Army Philadelphia Kroc Center and West Philly YMCA

https://www.teamunify.com/team/mapdrs/page/home

West Philly YMCA

Address: 5120 Chestnut St Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19139

Phone: 215-220-9199

https://www.philaymca.org/locations/west-philadelphia-ymca

Salvation Army Philadelphia Kroc Center

Address: 4200 Wissahickon Avenue, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19129

Phone: 215-717-1200

Email: PhillyKrocInfo@use.salvationarmy.org

https://easternusa.salvationarmy.org/philadelphia-kroc/

Make A Splash

Connect communities to swim lessons (including those that offer free and reduced-cost lessons) and raise awareness of the importance of learning to swim.

www.usaswimming.org/makeasplash

“Pool: A Social History of Segregation”

A 4,700 square foot museum exhibition that investigates the nation’s handling of race as it relates to public pools.

Address: 640 Water Works Drive, Philadelphia Pennsylvania (The Fairmount Water Works)

Phone: 215-685-0723

Black Hair Experience

Interactive selfie-museum that combines a pop-up art exhibit celebrating Black hair

Address: 630 Flushing Avenue, Suite #115. Brooklyn, NY 11206

Email: Hello@theblackhairexperience.com

(Locations also in Atlanta & DMV)

Alianza Americas

Network of migrant-led organizations working in the U.S. to create a better life for communities across North, Central and South America

Address: P.O. Box 23491

Chicago, IL 60623

Phone: 877-683-2908

Email: info@alianzaamericas.org

Aclamo

Provides support and resources for struggling families in Latino communities

Main Address: 512 West Marshall Street

Norristown, PA 19401

(Offices also in Lansdale & Pottstown)

Phone: (610) 277-2570

Email: info@aclamo.org