- Kroger is using a giant, robot-powered warehouse — instead of opening stores — to break into Florida, a new market for the country's largest supermarket operator.

- It plans to use the same strategy in the Northeast, where it will deliver online orders to homes and serve customers in New York, New Jersey and Connecticut for the first time.

- The automated sheds are a key piece of the company's growth strategy and an effort to turn e-commerce into a bigger, more profitable business in a notoriously low-margin industry.

GROVELAND, Fla.— Kroger wants to attract tens of thousands of new customers in Florida — and it plans to do that without opening a single grocery store.

Instead, the supermarket operator is relying on a giant warehouse of robots that help retrieve such products as bananas, milk and meat, and a fleet of delivery drivers that drop off online grocery orders at people's doors. The automated warehouse — big enough to fit nearly eight football fields — is a pricey bet for the grocer and an illustration of its e-commerce ambitions.

Get Philly local news, weather forecasts, sports and entertainment stories to your inbox. Sign up for NBC Philadelphia newsletters.

Three years ago, Kroger struck a deal with British online grocer Ocado to build a network of customer fulfillment centers, which it calls sheds, across the U.S. It chose Ocado because of its track record in the United Kingdom, where it's gained popularity with customers. Kroger has opened two sheds so far, with plans for at least nine more over the next two years.

Florida is ground zero as Kroger rolls out a national strategy to become a more dominant e-commerce player. It has invested at least $55 million just on construction of its shed alone. It has hired 900 employees and counting across the state. And it has announced plans to use the state as a blueprint to break into new markets and take on grocery rivals, including entrenched regional players like Florida-based Publix and retail behemoths like Amazon and Walmart with market values that are about 54 times and 13 times larger than Kroger.

Kroger has argued that the sheds will help it keep up with customers who are buying more food and household items online — while increasing the money it makes from each of those orders. With its Florida expansion, the grocer must not only prove the sheds can power a large, profitable e-commerce business in a notoriously low-margin industry, it must also win over customers in a brand-new market where some may not even know its name. It may be the largest supermarket operator in the country, but in the state, Kroger is the newcomer and, at least initially, the underdog.

Money Report

The playbook that the grocer is developing with Kroger Delivery in Florida will be useful as it expands the business to the Northeast. Last month, it announced plans to build a shed to serve customers in New York, New Jersey and Connecticut for the first time. It has not shared its timetable for that project.

'Once it's obvious, it's too late'

CEO Rodney McMullen, 61, joined Kroger in 1978 as a part-time stock clerk. He said the company must invest in digital and break into new markets to stay relevant.

In his office at Kroger's Cincinnati headquarters, he keeps a list of the top 10 food retailers over the past few decades. The company names and their rise — or fall — from the list remind him how quickly retailers can go from dominant to obsolete.

"Every time that it [the retail industry] transitions, there's going to be winners and losers," he said in an interview with CNBC. "And all you have to do is be the one that's in front of that trend change. And once it's obvious, it's too late."

'Tell your neighbors'

Kroger's delivery vans serve as giant billboards, signaling the grocer's arrival in Florida. Each work day, Latoya Thornton puts on her Kroger uniform and gets behind the wheel to shuttle orders to customers. The vans keep groceries chilled in the Florida heat, even on long drives to far-flung rural communities with dirt roads.

But a short drive from Kroger's central Florida shed is all it takes for Thornton to see the company's competition — and its opportunity. Publix, a Florida-based grocer, has billboards advertising its delivery service, which is powered by third-party delivery company Instacart. Nearby, construction cranes dot the landscape in new subdivisions with big banners that call out "New Homes Coming Soon."

The migration of people to the Sun Belt is why Kroger decided to plant its flag in Florida. Many Floridians have moved from other states where the grocer is already a household name, McMullen said, giving the company a quicker way to win business.

As U.S. population growth has slowed over the past decade, Florida has defied the trend with a more than 14% increase from 18.8 million in 2010 to 21.5 million in 2020, according to the U.S. Census Bureau. At least some of those new Floridians belong to wealthier households who moved to the state because of its low taxes — and they are an appealing customer base for grocers.

Kroger has nearly 2,800 stores across 35 states. In Florida, though, it has only one store, which is near the Georgia border. Elsewhere in the state, there are none of its many banners, which include Fred Meyer, King Soopers and Ralphs.

The Sunshine State is dotted with numerous Publix locations, a privately held grocery chain with deep roots and the largest share of the state's market, according to market research firm IRI, which tracks sales of consumer packaged goods.

Publix spokeswoman Maria Brous said the grocer has built a loyal following for more than 90 years. She said it will keep "evolving with our customers and meeting them where they are, in-store or online."

"Competition makes us all better, and our customers benefit the most," she said, when asked about Kroger's expansion.

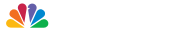

Publix rings up 37% of Florida's grocery sales, while Walmart has a 26% market share, according to IRI. That excludes categories that IRI does not track, such as prescription medications, apparel and fuel. And it doesn't include Costco and dollar store retailers.

Yet the market is still fragmented. Other grocers, including Aldi, Sprouts Farmers Market and Amazon-owned Whole Foods Market, see opportunity in Florida, too, and are opening new locations there.

Thornton said she realizes that part of her job is getting the word out about Kroger. At traffic lights, drivers sometimes honk at the delivery van, roll down their windows and ask for the location of the nearest store. She hands them business cards with delivery service details.

Some customers are homebound seniors or older residents who flocked to the state for the warm weather and moved into large retirement communities, such as The Villages. Others are busy parents or shoppers who see home delivery as a way to save time.

"I tell them the greatest tip you can give us is 'Tell your neighbors,'" she said.

McMullen said Kroger's online-only offering helps it stand apart. "If you go in with just physical stores, how do you distinguish yourself between what's already there?" he said. "By going into the market with a shed, it's really offering something that's not offered in the same way today."

Kroger Delivery's service fee starts at $6.95 per delivery, on top of grocery charges. Florida customers can sign up for Kroger's Delivery Savings Pass, an annual subscription service that costs $79 for unlimited delivery. To reel in new customers, Kroger has been dangling $15 discounts off of the first three orders.

Making the switch

McMullen declined to share how many customers Kroger has so far in Florida. He said it is "tracking ahead of where we thought we would be." The service also has high repeat rates — a reflection, he said, that customers are pleased when they use it.

New customers tend to order fewer items initially, McMullen said. Over time, the home delivery orders resemble curbside pickup, he said, with baskets about "three times the size of somebody going into a store."

One shopper who made the switch is Caitlin Zausner, a 35-year-old mother of two who lives in Bradenton — about 100 miles from Kroger's shed in Groveland. When the pandemic began, she was pregnant, juggling a toddler and trying to reduce her family's risk of getting Covid-19.

She stopped making frequent trips to her local Publix and started getting groceries through curbside pickup. Each Saturday, she put her 2-year-old, Emmy, in the backseat and drove to Walmart and a local farmer's market to retrieve online grocery orders.

As they waited in the parking lot, she played kid's music and kept dry Cheerios handy to keep the toddler busy. The weekly ritual took about an hour and a half.

That changed in June when Zausner read a Facebook post from a neighbor, who tried and liked Kroger Delivery. Zausner knew of Kroger from her sister-in-law who shops at its stores in Tennessee.

Even before the pandemic, Zausner said, she associated trips to the grocery store with stress: Will the baby sit in the stroller? Should she put her into a baby carrier? How will she keep her amused?

She placed an order and said she was impressed by the fresh produce and meats — and the slightly lower prices than Publix. Now, a Kroger delivery arrives each week and she can spend her Saturdays at the playground.

"It's just a hassle to carve out time to go [to the grocery store] and have a list," she said. "I don't miss grocery shopping."

Covering the costs

While Zausner is a fan, not all Americans are on board. Habits need to change for Kroger's risky bet to pay off. More than $1 billion for construction spending alone is on the line as Kroger looks to build 20 facilities across the country over time.

Then, there are labor costs. Despite the help from automation, Kroger must employ hundreds of pickers and delivery drivers, who are employees rather than gig economy workers. Driver pay starts at $19 an hour.

Meantime, Kroger pays Ocado an undisclosed portion of every sale as part of its agreement.

The grocer is banking on the premise that online grocery shopping will drive a larger and larger percentage of total grocery sales — and that customers will embrace home delivery.

At the moment, Americans tend to favor curbside pickup when they order online. That approach has financial incentives for consumers and retailers, since shoppers can skip fees and companies can reduce delivery costs.

Like other grocers, Kroger's online business took off when the pandemic began as consumers cooked and dined more at home. Its digital sales more than doubled in fiscal 2020 from the prior year. Kroger's shares are up 35% year to date, putting its market cap at $31.94 billion.

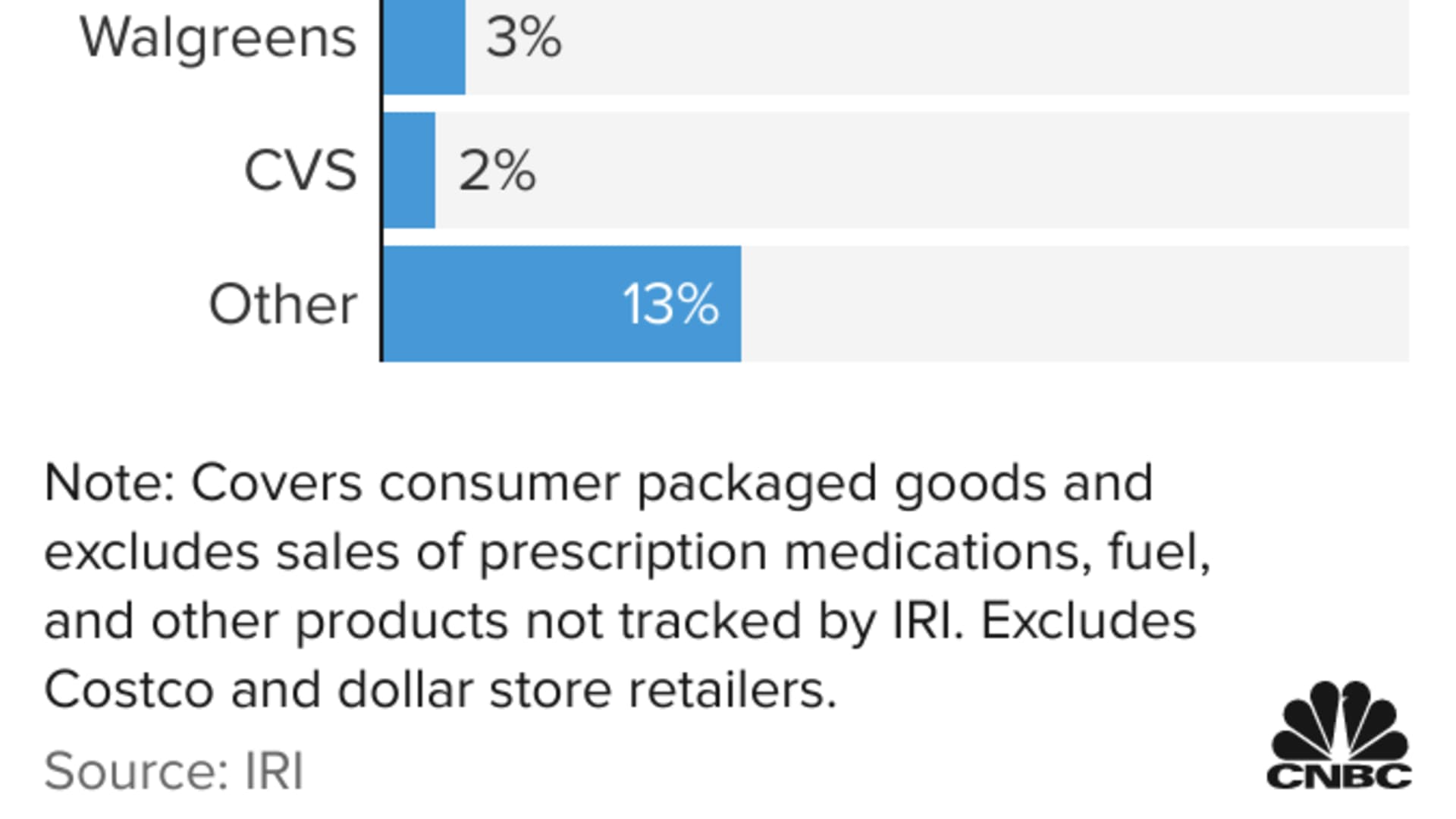

As consumers return to restaurants and travel, growth has tapered off for online grocery shopping, but it has persisted at a much higher level than pre-pandemic. About half of U.S. households — 64.1 million in total — bought groceries online through ship to home, delivery or pickup in September, according to a survey in late September by Brick Meets Click, an independent research initiative, and sponsored by Mercatus, a digital commerce tech provider.

Online grocery orders now drive 12.3% of all grocery sales versus 1.8% pre-pandemic, according to the polling done by Brick Meets Click/Mercatus. That translates to $8 billion of roughly $65 billion in monthly grocery sales.

Online grocery shoppers placed an average of 2.76 orders in September — a higher and more stable number than a year ago, its surveys said.

Kroger points frequently to Ocado's success on its home turf. British shoppers have embraced online grocery shopping more than Americans and generally favor home delivery instead of pickup.

In the U.S., Kroger has said the sheds can churn out orders for curbside pickup, too — at least in markets where it has stores. This is already happening in Ohio.

Karen Short, a retail analyst at Barclays, said the landscape has changed dramatically since Kroger struck the Ocado deal. At the time, she said, Kroger felt an urgency to catch up to Amazon and Walmart. It was nearly a year after Amazon bought Whole Foods, a move that spooked legacy grocers. Meanwhile, Walmart was investing heavily in its e-commerce business.

Now, Short said, grocers can opt for lower-cost solutions. Walmart, for instance, the country's largest grocer by revenue, is carving out parts of its stores and turning them into mini, automated warehouses — a strategy called micro-fulfillment. Albertsons struck a deal with third-party delivery company DoorDash.

"The problem you have now is Kroger is locked into this high capital expenditure commitment," she said.

Plus, she said, construction costs have likely ballooned from the grocer's initial projections as the price of materials and labor rise. (Kroger declined to comment on the final cost.)

Short estimates that Kroger pays 4% or 5% of every dollar of sales to Ocado — less than the estimated 8% it had paid Instacart in 2018 when it signed the deal with the British online grocer. She said that lower fee is now likely in line with third-party players like Uber Eats and DoorDash, which could fulfill orders without the need for sheds.

She has a sell rating on Kroger, with a price target of $37. That's roughly 14% below where Kroger closed Wednesday.

For grocers, including Kroger, a big challenge is turning e-commerce sales into ones that are just as profitable — or more profitable — than a sale at a store, even while taking on additional labor and delivery costs.

Kroger has said each shed will break even in its third year of operations and by the fourth year, it will match the profitability rate of a store. And it's said one shed is equal to 20 stores worth of sales, but with only 60% of the capital and labor.

Matt Fishbein, retail analyst at Jefferies, said hitting that benchmark will be the grocer's biggest challenge. If it doesn't bring down the cost of fulfilling online orders, the addition of sheds in its current grocery markets could potentially divert foot traffic away from its stores and toward a sale that makes less money. He has a hold rating on Kroger, with a price target of $40. That's about 7% below where shares are currently trading.

Short said Kroger's Ocado deal could play out best, however, in new markets like Florida where it can gain share without cannibalizing store sales. In regions like Florida, the Northeast and Northern California, she said Kroger can beat rivals on price.

"There's pockets of the country where if you can do it and undercut your competitors and still maintain your margin — even with the fees that you pay Ocado — it seems kind of like a no-brainer," she said.

Fishbein said Kroger's first-party approach could give it an advantage over other grocers that use third parties, even though that comes with higher costs. He compared it to restaurants that rely on delivery companies and give up aspects of customer service, such as making sure that food arrives hot and having the data to make product recommendations or communicate directly with that customer.

But Fishbein said simply recruiting customers could trip up Kroger. Some shoppers are already hesitant to buy items like steak and fruit online, since they prefer to check for quality and ripeness.

"Why would you think that Kroger delivering it is going to be fresher and better than you just getting off your butt, getting in the car and going down the street to Publix?" he said.

The Ocado deal is just one facet of its e-commerce strategy, McMullen said. The company also recently signed an agreement with Instacart to offer deliveries in as little as 30 minutes nationwide.

Kroger is already doubling down on Florida. It will add two smaller-sized fulfillment facilities to serve the southern part of the state. It already has two hubs in Jacksonville and Tampa where fleets of additional trucks can take filled orders and fan out from there to help expand its delivery area. One of these new sites will be a micro-fulfillment facility powered by Ocado.

The expansion will allow it to deliver to customers in as fast as 30 minutes with an assortment of 10,000 items and to deliver same-day and next-day orders with 35,000 items, Kroger said. It hasn't disclosed the timetable for this project nor its costs.

McMullen shakes off the naysayers. He said he finds the speed of change in his longtime industry energizing.

"The customer is going to win, because the customer is going to be able to get what they want in an easier way," he said. "And to me, I think it's cool to be in the middle of that."