- Economists expect the Russia-Ukraine conflict to trigger higher global inflation but probably not a recession.

- The importance of the two nations as agriculture exporters and producers of elements key to semiconductor manufacturing will exact an economic toll.

- Broadly, though, Russia's total economic output is a little smaller than New York state's, while Ukraine's GDP is about the size of Nebraska's.

- Markets still largely expect the Fed to begin raising interest rates in March and continue doing so through 2022 and into 2023.

Food and gasoline probably will cost more and the supply chain issues that have bedeviled the economy for the past two years likely will persist or even intensify.

But could the Russia-Ukraine conflict somehow tip the U.S. economy into recession? It seems unlikely at this point, though anything is possible.

"What we've seen is oil prices have gone up, and equity prices at least initially retreated on all of this. Together, that's a mild — stress mild — stagflationary hit to the economy," Wells Fargo chief economist Jay Bryson said. "It's going to push inflation higher than it is, and it's probably going to slow growth. But it's probably not enough to push the economy into recession."

Get Philly local news, weather forecasts, sports and entertainment stories to your inbox. Sign up for NBC Philadelphia newsletters.

That view is in line with most Wall Street economists.

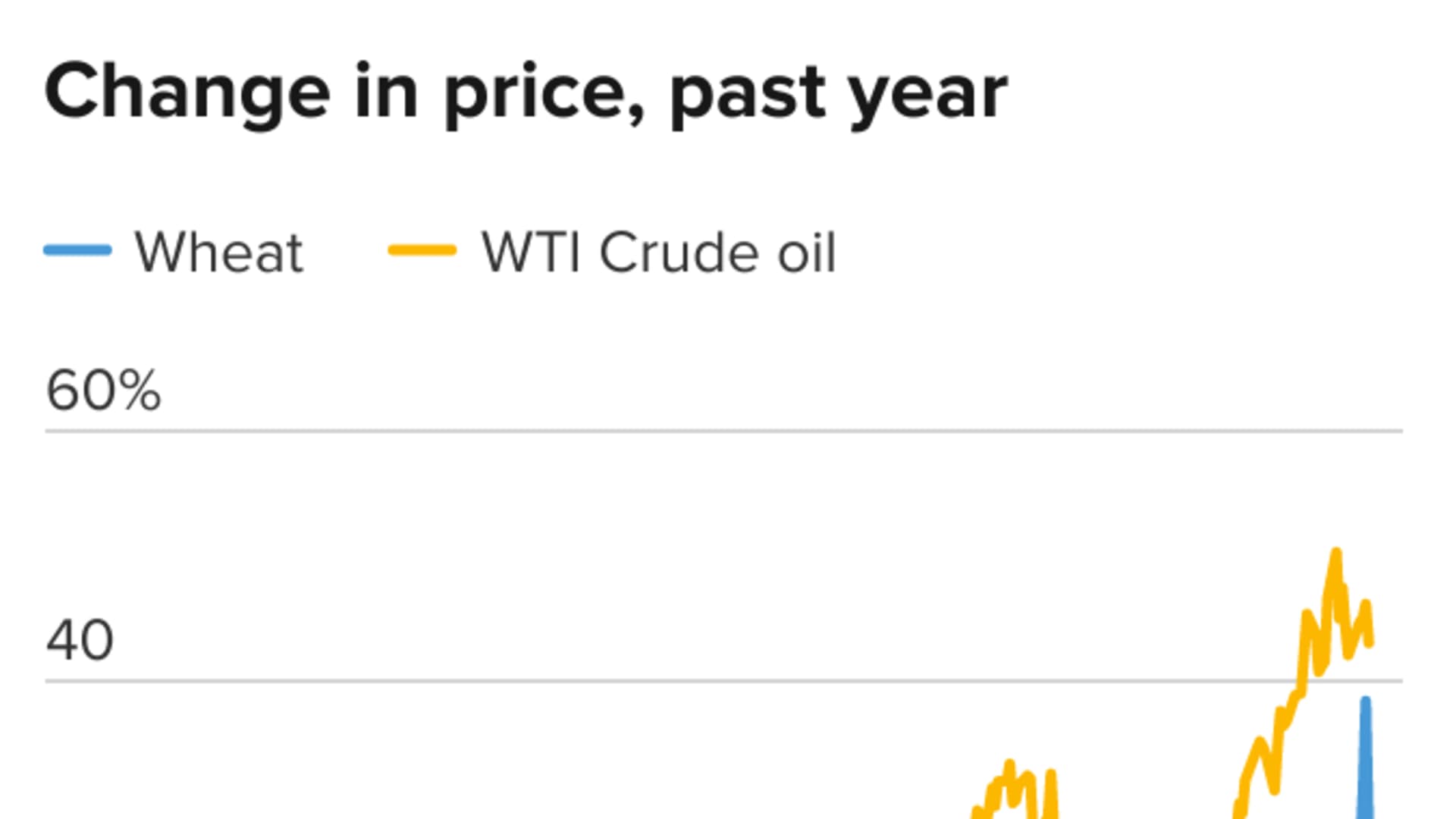

Nevertheless, at a time when inflation is running at its highest level since the early 1980s, the last thing consumers need is more price pressure. Grain and energy commodity prices catapulted higher in recent weeks, bringing West Texas Intermediate prices up about 22% in 2022 and wheat up by double digits, before receding sharply Friday.

The importance of the two nations as agriculture exporters and producers of elements key to semiconductor manufacturing will exact an economic toll. But the implications shouldn't be major for a global economy that's still in a rebound phase from the depths of the pandemic.

Money Report

"Higher gasoline prices — that will affect consumer confidence. Does that mean the consumer is going to lock down spending? Probably not," Bryson said. "Given the fact that omicron is receding and things are opening up, I think that's a countervailing force."

Two comparatively small economies

Neither country is a huge economic force, despite their abundance in agricultural products and Moscow's military might.

Russia's total economic output is a little smaller than New York state's, while Ukraine's GDP is about the size of Nebraska's. Combined, the two countries are responsible for up to 30% of the world's wheat exports and 80% of the global sunflower seed production, according to Capital Economics.

The tensions have roiled financial markets, coming as they do at a time when investors already were worried about tighter policy from inflation-fighting central banks including the U.S. Federal Reserve.

"The key effect will come through higher oil and natural gas prices," Capital Economics forecasters said in a note to clients. "It now looks like average advanced economy inflation could still be as high as 4% by December ... Policymakers will be weighing the upside risks to inflation against the downside risks to activity."

Markets still largely expect the Fed to begin raising interest rates in March and continue doing so through 2022 and into 2023. Pricing has been volatile, but traders see up to seven quarter-percentage-point hikes this year, which would equate to one at each of the Federal Open Market Committee meetings.

That prospect had been enough to whack stocks this year and send government bond yields surging higher. Combining that with geopolitical turmoil could make for a bad mix.

"The impact via tighter financial conditions is the most unpredictable," Goldman Sachs economists Joseph Briggs and David Mericle said in a note. "Past geopolitical risk events have only rarely been followed by a meaningful tightening in U.S. financial conditions, though it is hard to generalize to the current situation. A larger tightening in financial conditions and an increase in uncertainty facing businesses would further weigh on U.S. growth."

Goldman estimates each $10 per barrel increase in oil would raise core inflation excluding food and energy by 0.035 percentage points and headline inflation by 0.2 percentage points, but exacts just a 0.1 percentage point hit to U.S. GDP, which is coming off its fastest full-year growth since 1984.

"The growth hit could be somewhat larger if geopolitical risk tightens financial conditions materially and increases uncertainty for businesses," the economists said.

However, Goldman said it doesn't expect the events in Ukraine to deter the Fed from hiking. Past crises sometimes have triggered the Fed to ease policy, but "inflation risk has created a stronger and more urgent reason for the Fed to tighten today than existed in past episodes," the firm said.

Indeed, most Fed officials who spoke this week said they are watching the events, but they didn't indicate that they would change their mind about tightening. Fed Governor Christopher Waller said Thursday that "a strong case can be made for a 50-basis-point hike in March" if the economic data continues to show a strong labor market and persistent inflation.

Richmond Fed President Thomas Barkin earlier this week compared the current conflict to Russia's annexing of Crimea in 2014 and said that event had little economic impact.

"If this evolves like 2014, I don't think you're going to see much change to the underlying logic that I've talked about," Barkin said. "But this is uncharted territory and we'll have to see where the world goes."