What to Know

- In 2014, 94 percent of financially secure Americans said they were registered to vote.

- By contrast, 54 percent of low-income people said they were registered.

- In Philadelphia’s last mayoral election, just 24 percent of residents voted.

Voting would be nearly impossible for South Philadelphia resident Eric Drummond if his polling station was not around the corner.

Disabled by diabetes and a motorcycle accident, Drummond depends on his wife, who has a bad back, to push his wheelchair. But the thought of losing health care is enough to drive them both to the polls on Nov. 6, Drummond said.

“My medication went up and I’m on a fixed income,” he said. “I can’t really move my hands but they’re talking about taking away Medicaid and Medicare.”

This is the reality of voting while broke. Many low-income Americans face increasing uncertainty when it comes to casting a ballot, from feeling politically disengaged to questioning whether they have the time and resources to find their polling place. As a result, millions of potential voters opt out of an electoral system they feel doesn’t serve them well.

Local

Breaking news and the stories that matter to your neighborhood.

In 2014, 94 percent of financially secure Americans said they were registered to vote compared to 54 percent of low-income people, according to the Pew Research Center. The numbers extend to political engagement, as well. Just 14 percent of low-income people have contacted an elected official in the last two years while 42 percent of wealthier Americans have done this, Pew concluded.

This is where 32-year-old Anton Moore comes in. As Philadelphia’s youngest ward leader, Moore canvases his West Passyunk neighborhood weekly to speak with residents and encourage them to vote. He isn’t surprised when people don’t answer the door.

“It’s tough, but you do what you can,” he said while walking up and down streets on a rainy October Sunday.

When he patrols the neighborhood, Moore carries a “hit list” of registered voters. He diligently knocks on every door, waits for an answer, introduces himself if someone comes out and then moves on to the next house. Rinse and repeat for several blocks.

It was during one of these outings that Moore paused to chat with Paul Verwey. The 23-year-old moved into the neighborhood with his fiance about a month ago, two small dogs and plans for a growing family in tow. But soon after buying their first home, Verwey lost his job. Suddenly, their future was in question.

“That goes to your head,” he said. “It completely changed my perspective - you just never know what position somebody’s in.”

Prior to losing his job, which paid nearly $90,000 a year, Verwey said he questioned people who required financial help from the government. Now, he plans to vote for candidates who are “understanding of the situations that people are in,” Verwey said.

“There is a lot of divide across the country as a whole,” he said. “It’s very important for us to know that we’re going to be raising our children in a society that is going to be accepting of them and also supportive.”

Both Verwey and Drummond are registered voters who intend to visit the polls in November. But more than 21 percent of eligible voters were not registered for the 2014 federal elections, according to the U.S. Census Bureau. Similar data is not yet available for the 2018 midterms because of rolling state deadlines.

Moore is accustomed to encountering so-called voter apathy. A familiar refrain during his weekly canvassing starts with someone saying their vote doesn’t matter and, with any luck, ending with a promise to register. But on this particular day, voter registration had already ended in Pennsylvania and several neighbors told him they didn’t even know an election is just around the corner.

“When is the election?” one man, who did not want to be identified, asked Moore.

“Nov. 6,” Moore answered.

“The vote is not for presidential, right?” the man asked. “Because I don’t know too much about the governors, to be honest with you.”

Moore went on to introduce the gubernatorial candidates. The man sounded interested, explaining that his first time voting was in the 2016 presidential election after he became a U.S. citizen.

“We could really use you at the polls,” Moore concluded, promising to return soon to help this neighbor learn about the candidates.

Local elections are nearly always a hard sell for voters. In Philadelphia’s last mayoral election, just 24 percent of residents voted, according to researchers at Portland State University, who examined voter engagement across the nation’s biggest cities.

But this year, the midterm elections will determine who controls Congress. In Pennsylvania, these numbers are especially significant after the state Supreme Court created new congressional districts, forcing many voters to consider different candidates for the first time since 2010.

Pennsylvania's newly drawn 1st Congressional District, for instance, is nearly evenly split between Democratic and Republican voters.

It's the kind of place where a moderate congressman like Republican Rep. Brian Fitzpatrick has, in the past, appealed to centrist voters of both parties.

But Fitzpatrick's vote in favor of President Donald Trump's tax cut last year didn't sit well with Jerry Middlemiss, a moderate Democrat from Yardley. And he is the kind of voter Fitzpatrick would need to win over to eke out a win this November.

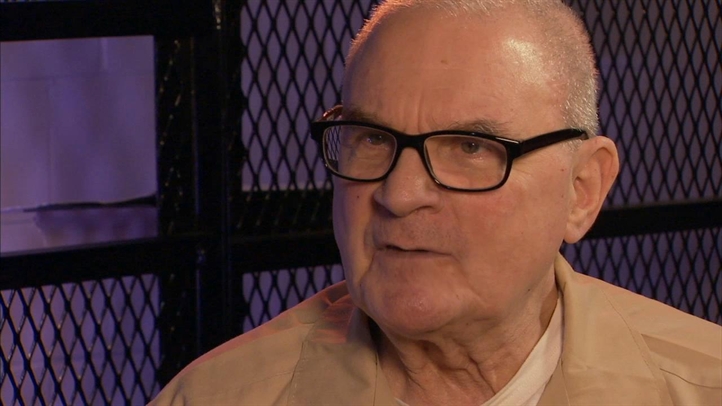

"I'm not pleased about that," the semi-retired school counselor said.

Middlemiss doesn't yet know much about Scott Wallace, the Democrat challenging Fitzpatrick, but he believes America should push the reset button on Congress. And there is only one way to do that this year.

"If you are opposed to the current administration and the way the government has been run, you may want to make a change," Middlemiss said.