You’re walking down Broad Street, heading toward the subway when you’re accosted by a masked man. He points a black handgun at your chest.

“Give me your money,” he demands.

You start to reach into your pocket. But then something goes horribly wrong.

A loud crack rings out. Pain shoots through your chest as you fall to the ground. Out of the corner of your eye you see your robber’s feet pound the concrete as he runs away.

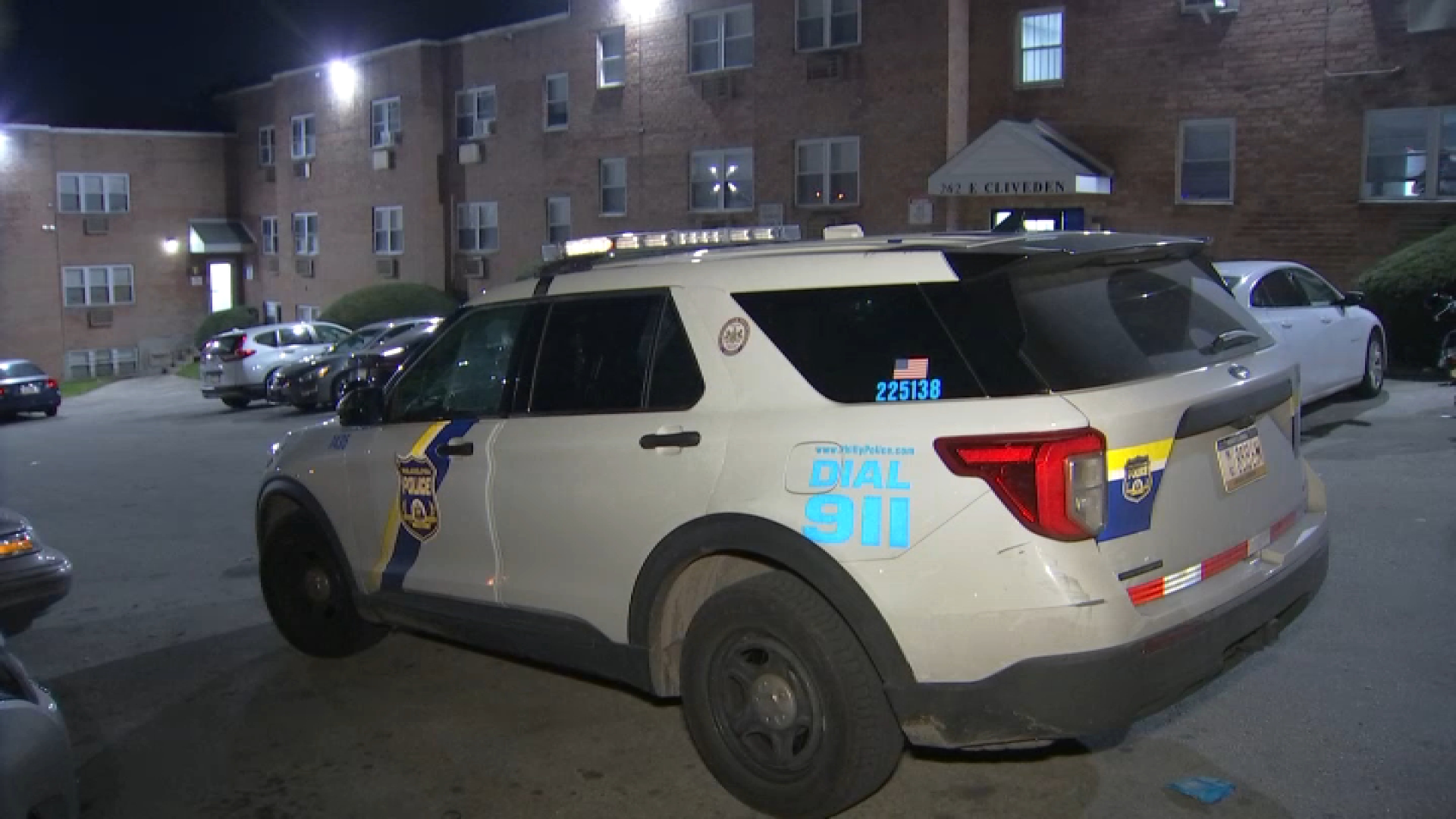

Witnesses rush to you. They call 911. A police officer arrives in moments, before firefighters and paramedics can get there. Now the officer must make a choice: wait for the paramedics to arrive and offer advanced medical care or put you into the back of the police cruiser and speed you to the nearest trauma center.

Which is better?

Local trauma experts believe getting you to the hospital right away could offer you a better chance of survival. And they’re planning to launch a first-of-its-kind citywide study to answer the question once and for all. It’s a study that is bolstered by what police are already doing and could change how paramedics treat certain gunshot and stabbing victims.

Local

Breaking news and the stories that matter to your neighborhood.

“We think it’s very helpful in a very specific trauma patient population,” Dr. Amy Goldberg, head of trauma care at Temple University Hospital, told NBC10 Tuesday. Goldberg is leading the study efforts along with trauma fellow Dr. Zoe Maher.

Evidence suggests carrying out standard field procedures like inserting a breathing tube or providing fluids intravenously to victims suffering from penetrating wounds — being shot or stabbed — between the neck and the knees can be detrimental.

“In those patients that are bleeding and have a low blood volume, if you put a breathing tube in and bag them, you may be decreasing their blood pressure even more,” Goldberg said.

“If you have a patient who is bleeding and you put an intravenous line in and you pump their pressure up with that intravenous line because you’re giving them fluids, you may dislodge any clots that are there and cause more bleeding,” she said.

In the study called the Philadelphia Immediate Transport in Penetrating Trauma trial, paramedics working in city ambulances that provide advanced life support will be instructed by dispatchers to either carry out normal medical procedures on patients that fit the criteria or immediately take them to the hospital.

The medics will be exempt from obtaining informed consent from patients — meaning victims won’t be asked if they’d like to take part in the research.

“It’s not like you can have a patient that’s shot on the street, who has a low blood pressure and high heart rate, and we say ‘Sir, we’d like to enroll you in our study,’” Goldberg said.

But the exemption allows the study to be truly random and provide the strongest results, according to Goldberg.

Thirty-seven percent of Temple’s trauma patients arrive to the emergency room by either police or private vehicles. Not all are victims of penetrating wounds to their torso, but doctors say a good chunk are. The hospital carried out prior studies that looked at patient data and ones that simulated penetrating wounds on animals, but none were this extensive.

“We don’t want to go on antidote and we don’t want to rely on retrospective studies and animal studies,” Goldberg said. “We do believe in our hearts that this is the best way to take care of patients to save their lives.”

Temple researchers are teaming up with colleagues at each of the city’s trauma centers — Penn, Hahnemann, Jefferson, Albert Einstein and Aria — and the Philadelphia Fire Department to carry out the trial. It’s the first time they’ve all worked together on this scale.

“We’re trying to get smarter about what we’re doing,” said Dr. Patrick Kim, Trauma Program Director at Penn Medicine. “Sometimes smarter means doing more and different procedures and sometimes it means not doing more procedures.”

If researchers’ hypothesis turns out to be true, it would most likely lead to changes to how not only local paramedics treat these victims, but also their counterparts in cities across the United States.

The city has conditionally approved the study and expects to provide final approval soon. Philadelphia Health Commissioner Dr. James Buehler tells NBC10 any project where informed consent is forgone gets extra scrutiny from city officials.

Goldberg said citizens will have the opportunity to opt out of the study. After registering with researchers, they will be provided a rubber wrist band that tells paramedics they would not like to participate.

Researchers expect the trial to last up to three years and plan to collect data from 780 participants. It will begin after undergoing three months of community outreach notifying citizens study will be taking place.

Contact Vince Lattanzio at 610.668.5532, vince.lattanzio@nbcuni.com or follow @VinceLattanzio on Twitter and Facebook.